| Software and Computer Systems Company, LLC |

Activity Monitor is an application provided with all

versions of Mac OS X since MacOS 10.3 (Panther) that allows a

user to view, among other things, CPU usage, memory usage, disk

activity, disk usage, and network activity. Activity Monitor

can, in many cases, be used to help isolate applications that

are consuming too many of these resources. It typically cannot,

however, help identify hardware problems. The goal of this

article is to introduce users to Activity Monitor and

illustrate the basics of using it and how to identify

performance problems with a system.

Activity Monitor is a process monitor. Every time a user

turns on their system and allows it to boot up, it is, at a

given instance, running dozens, if not hundreds, and in some

cases even thousands of processes. Some processes are started by

the system at boot time and run continually while the system is

operating. Some processes may be launched periodically,

typically at fixed intervals, to perform a specific task. Other

processes are launched by the user themselves. Activity

Monitor will sample these processes at fixed time

increments and all the user to obtain a "snapshot" of activity

each time Activity Monitor does its sampling. A

process, or application must be running in order for Activity

Monitor to detect it.

A process is, in a nutshell, a running program. All processes

are assigned a process identification number, or PID. When a

process is running it will consume CPU resources and memory, and

may additionally use disk and network resources. Most people

don't need to monitor processes unless there seems to be

something going wrong with their systems. The terms process and

application may be used to mean the same thing.

One special process, called the kernel, is the first process

started by a system and always has a process ID of 0 and a

process name of kernel_task. Once the kernel is started,

it in turn launches another process named launchd which

is responsible for launching virtually every other system

process that will be run on the system. Processes launched by launchd

may directly or indirectly run other processes as well. Once all

of these boot sequence and start up processes are running, your

system is ready to be used. Most people are unaware of any of

these processes unless they use a tool like Activity Monitor

to obtain information about them.

When you double click on an application icon to launch it, you

are indirectly starting at least one process. The icon that you

double click on to start the typical application is not really

an application, it's a special folder that contains not only the

code to launch one or more processes, but also resources that

the processes may use, such as icons, help files, fonts, etc. An

application process may itself run other processes if needed.

Processes running on a system may or may not have names that

appear to make sense to the user. For example, when you launch Safari,

its process name will likewise be named Safari. Newer

versions of Safari will also launch another

process named

Safari Web Content. Other processes have more obscure

names, such as mds (the meta data server used by

Spotlight) or usbmuxd (the process that handles USB

activity.)

The most common reason Activity Monitor is used is to try to determine why a system that was once functioning properly has become exceptionally slow. Performance losses are typically due to excessive CPU use by a process and its siblings, excessive memory consumption, excessive disk activity, or excessive network activity. In many cases, particularly on laptop computers, if the system starts overheating and the cooling fans are turning on too frequently, it's likely that the CPU is being overloaded. Hardware problems, such as a failing hard drive may also produce similar symptoms, and this will be dealt with a little later.

Activity Monitor is located in the Utilities folder contained in the Applications folder. Newer versions of OS X will have give direct access to the Utilities folder by clicking on the "Go" menu bar item in Finder and then clicking "Utilities" which will open up the Utilities folder directly. Older versions of OS X will require that you open up Applications first, and then open up the Utilities folder. Once the Utilities folder is open, simply double click on the Activity Monitor application icon, and it should start.

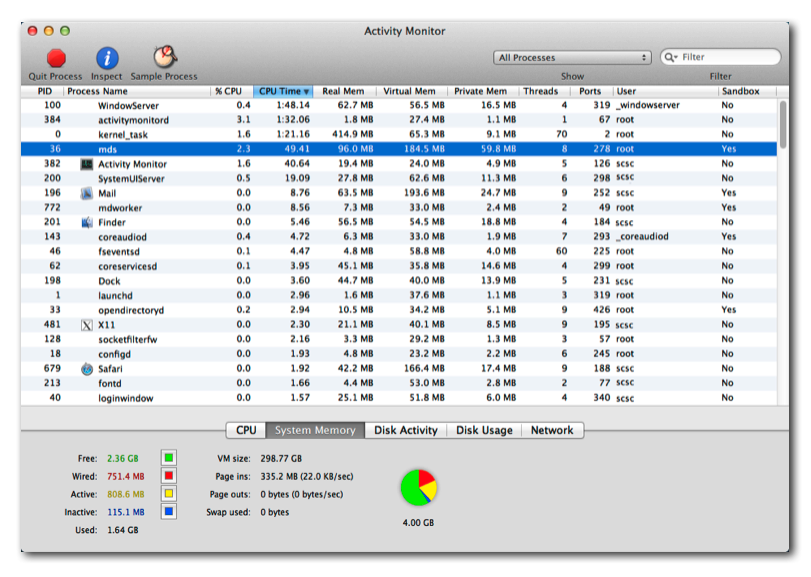

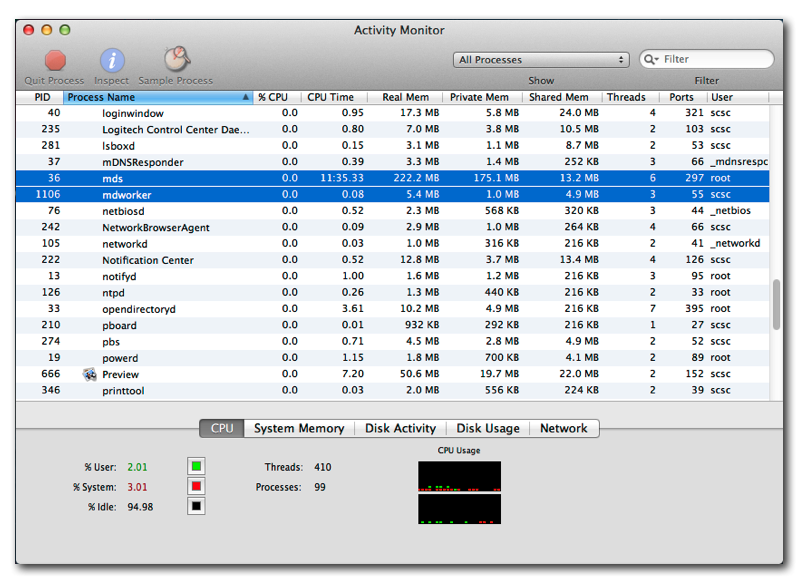

Once Activity Monitor has been started, the user interface should appear and be similar in appearance the the screen shot below.

We've observed that some versions of Activity Monitor will

require the user to click on the "Window" option of the Activity

Monitor menu bar to bring the user interface up.

To best appreciate this tutorial, open up

Activity Monitor now and follow along.

The top section of Activity Monitor allows you to quit a

selected process, inspect a process, sample a process, and

select which processes to observe. The middle and main section

of the interface reports on the activity going on in the system.

The bottom of the interface allows you monitor CPU usage, memory

consumption, disk activity, disk usage, and network

activity. We will describe these in detail from the top to

the bottom of the user interface.

Going from left to right in the top section of the user

interface, you'll see four buttons labeled Quit Process,

Inspect Process, Sample Process, all bundled in the left

section of the interface, and a process selection button on the

right half of the user interface. The process selection button

typically says "My Processes" on it the first time Activity

Monitor is invoked by a user. All the buttons on the left

will only become active when a process is selected from the list

of processes displayed in the mid section of the user interface.

The Quit Process button will allow you to

terminate a process. Any of the processes in the mid section

displaying the list of running processes can be highlighted by

clicking on them, and after doing so the normally grayed out Quit

Process button will become active. If you click on it, a

dialog will appear asking if you wish to Quit the

process, Force Quit the process, or Cancel the

operation. This is a potentially dangerous button because it

can terminate system processes which may render the system

dysfunctional, or in some cases even shut it down. Quitting a

process should only be done on processes that are not system

processes.

The Inspect button allows you to open up a dialog

window with more details on the process. This button will be of

more use to developers than the average user, and generally

shouldn't be needed.

The Sample Process button will sample the

selected process and show the amount of time the process spends

in various methods and libraries. It's typically only of use to

developers.

The process selection button on the right hand of the top

portion of the user interface will allow you to select which

processes are being displayed. Its label will typically read one

of the following:

All Processes: If this is selected, the

every process that's running on the system is being displayed.

This is typically what most users will want use.

All Processes, Hierarchically: All processes are

displayed with respect to the processes that launched them. If

you select this option, you will notice that the kernel_task

stands by itself, with launchd, the launch daemon,

parenting virtually everything other process running on the

system. For most people, this won't be of much value unless a

running application has launched another process that's become

problematic. In this case, viewing the hierarchy can indicate

whether or not the offending process was launched directly or by

another process or application.

My Processes: This will display all processes that

have been launched either directly by you, or on your behalf by

the operating system.

System Processes: This option will

display all processes started by the operating system.

Generally, none of these should be terminated using the Quit

Process option previously described because they it may

render the system or some system features dysfunctional, and

possibly crash the system.

Other User Processes: Some of the processes

started by the system are done using a system ID unique to that

process. Any process launched using such an ID will use that ID

and fall into this category. This is generally only of use to

developers and system administrators.

Active Processes: This option will list all the

active processes each time Activity Monitor samples

activity. The operating system, as well as applications, may

start and stop a number of processes for a host of minor tasks.

Additionally, during a process sampling, some applications may

go from an active to an inactive state. For these reasons, the

list will expand and contract frequently. This option won't be

of much use to us for this article, but it's interesting to

watch for a few minutes to get a feel for how the operating

system is constantly launching and terminating processes, and

some applications go from an inactive to active state with the

user is unaware of it.

Inactive Processes: This option is the exact

opposite of Active Processes in that it shows those that

currently aren't active at the time of sampling. This list of

processes will also expand and contract. This won't be of much

use to us for this article.

Windowed Processes: This will list all the

applications that are active on the desktop, including Finder.

This can be of some use if problems are associated with a

specific application that runs on the desktop because it can cut

down on some of the clutter presented by other processes.

However, many windowed (or desktop) applications can also launch

other processes that may not show up in this list.

Selected Processes: You can select a number of

processes from the process table by command-clicking on each one

that you want to monitor and then selecting this option. Activity

Monitor will display activity for only the selected

processes. This option is extremely useful, especially if you

want to see if you can duplicate the behavior of a poorly

behaving application. For example, if you thought Safari

was eating up too much memory, you could command-click on Safari,

Safari Web Content, and other applications Safari

may launch, such as Flash Player and then select this

option, and it will display only the activity associated with

these applications. However, if any of the selected processes

launch other processes, they won't show up in the list, so this

option should only be selected if you want to observe specific

processes and aren't concerned with anything else they may

launch.

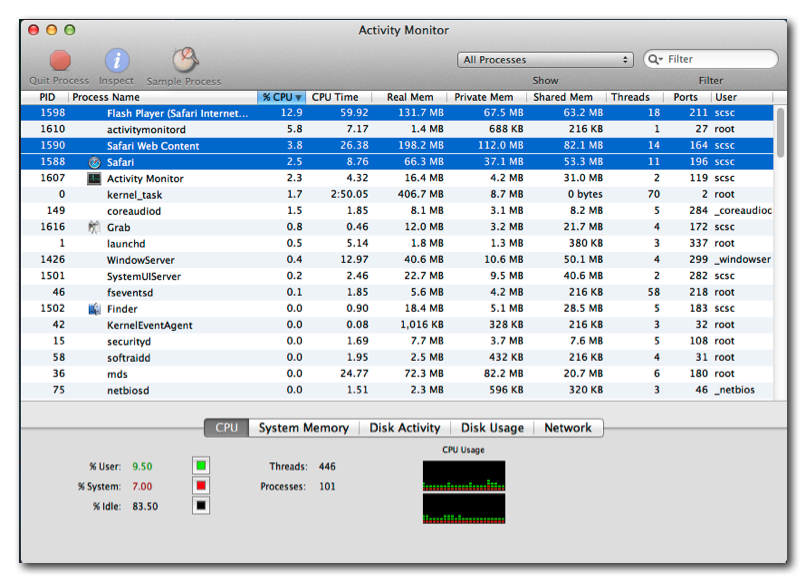

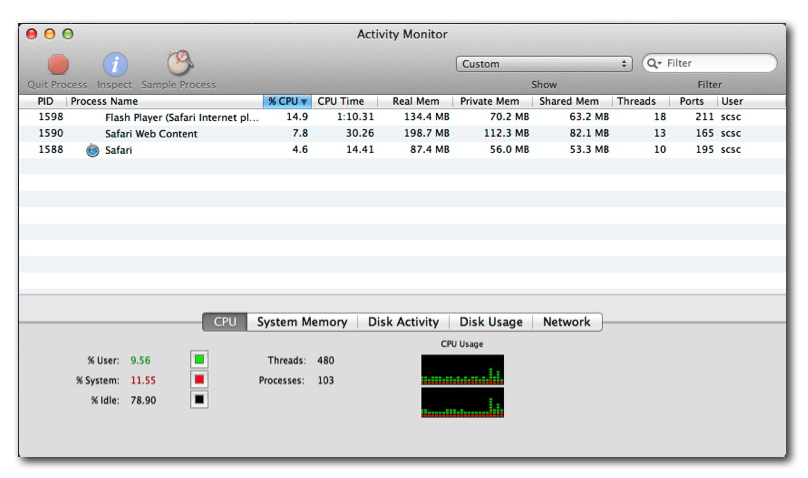

The following two screen captures of Activity Monitor illustrate the process of highlighting and then selected processes associated with Safari.

In the screen shot above the processes currently associated with

Safari while watching a YouTube video have

been selected. This was done by viewing all the processes with Safari

active, clicking on the %CPU column, to order them by the amount

of activity, and then command-clicking on each one to select

them.

Once the processes are selected, in the upper right corner,

change the process list from All Processes to Selected

Processes. After doing so, the Activity Monitor

changes to display only the targeted processes, and the process

list now says Custom.

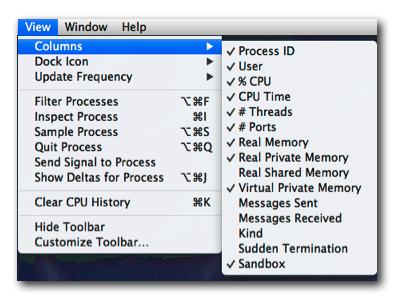

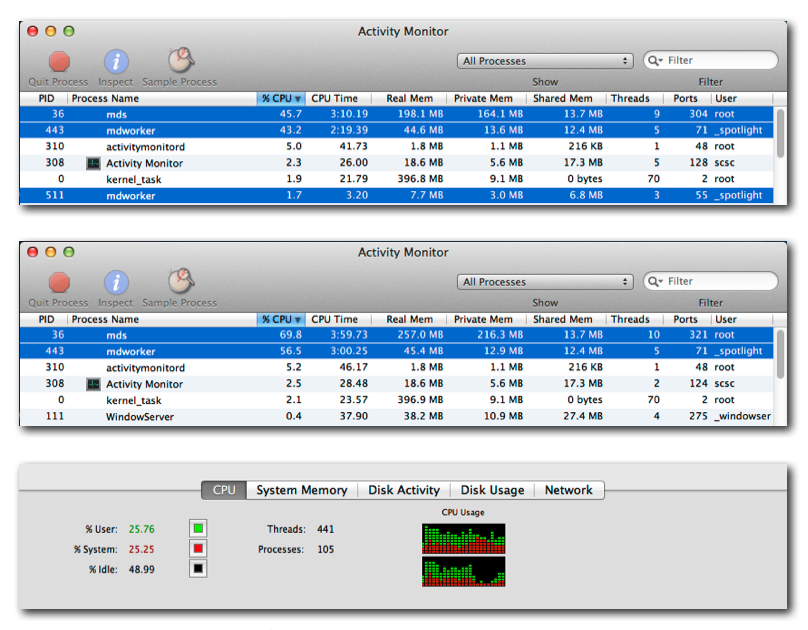

The mid section of the user interface, which occupies the

majority of the application, is the list of processes being

monitored. This is fully configurable from the Activity

Monitor menu bar by selecting the View option

followed by

Columns. The screen shot below shows this menu item

selected.

The columns that you choose to display can be moved around in

the user interface in any order you want to present them by

clicking on the column head and dragging it into the location

you desire. The width of the columns can also be adjusted.

For the purposes of this article we'll use the following:

PID: The process ID number

%CPU: This indicates the percentage of CPU usage

used for each process during Activity Monitor's sampling

snapshot.

CPU Time: This is the total amount of CPU time the

process has used since being launched, This is not the amount of

time the application has been running.

Real Mem: This is the amount of real memory the

process is actually using, and it often changes between Activity

Monitor samplings.

Private Mem: This is memory private to the

process.

Shared Mem: This is memory shared by the

application and other threads or processes running on the

system.

Threads: A thread is called "lightweight process"

in that it acts like another process launched by the

application, but still shares resources with the application

that started it. Threads can terminate on their own or be

terminated by the process that started them.

Ports: This is the number of ports the process is

using. Ports can be associated with network connections,

devices, and files, to name a few.

User: This is the short (Unix) name of the user

that's associated with launching the process.

The order of the processes may be rearranged by parameter by

clicking on one of the column headers. For example, if you want

to view the processes in alphabetical order, click on the column

header Process Name. To arrange the processes in order

of real memory consumption, click on the header Real Mem.

To determine which processes are currently using the CPU the

most, click on the header %CPU. The order may be

reversed by clicking on the column a second time. Remember to

adjust the scroll bars on the side of Activity Monitor

to position the list of processes at the top. As you'll see

later on, this feature can help us find problematic

applications.

Along the bottom of the user interface is a tabbed selector with

the titles CPU, System Memory, Disk Activity, Disk Usage, and

Network. Each of these presents data in a graphical

manner, instead of being tied to a specific process or

processes, it's reporting on the system as a whole. Details

regarding each option are as follows:

CPU: The dynamic graph shows the amount of

CPU resources being dedicated to user and system processes, as

well the the idle state, which is an indication of how busy the

CPU is. During levels of intense CPU activity, these figures

will often peg up to the top of the graph. There will be one

graph for each processor core. Most systems currently have 2

processor cores, so they'll have 2 graphs.

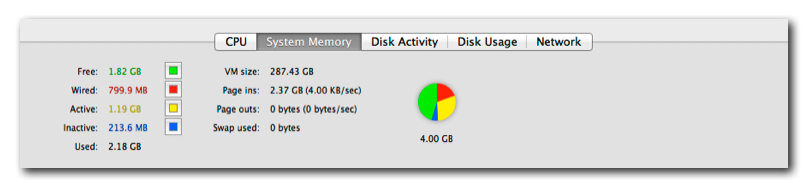

System Memory: This is probably the most important

graph that you'll need if you're system is having memory

problems of some type. The Free memory is just what it says it

is: memory that's not in use and is available to be used. The Wired

memory is the memory that's in use and can't be swapped out

because it's critical to the operation of the system. The Active

memory is memory that's in use, but can be swapped out because

the process associated with it is not critical to the operation

of the operating system. The Inactive memory is RAM that

was in use by a now terminated process, but the operating system

is hanging onto it to speed up the re-launch of the application

if it's started again. Inactive memory is essentially

free memory and can be reclaimed if the operating system or

other applications need it. To the right of these are the VM

size, which can generally be ignored, the Page ins,

which can also often be ignored, the Page outs, which is

an indication of pages being read from disk and restored to RAM,

and the Swap used.

Disk Activity: Disk activity displays how much the

drive is being accessed for reading and writing. Excessive disk

activity can indicate that the system is low on memory and is

swapping memory contents from RAM to disk, and back again, as

needed to keep applications running. High activity is also

associated with disk intensive applications, such as Spotlight

indexing. Notice that the "peak" indicator at the top of this

graph may change with activity, so at times it might be somewhat

tricky to interpret.

Disk Usage: This illustrates how much of your

bootable volume is used.

Network: This illustrated the amount of network activity

going on in the system. Like the Disk Activity graph,

the indicated peak on the top of the graph can change with load,

so it can be tricky to monitor.

From a user standpoint, performance problems will exhibit one or

more of the following symptoms:

Slow Loading Times: Slow loading times occur when

an application that used to load within a certain time frame,

such as a few seconds or less, is now taking much longer to load

- tens of seconds or perhaps even minutes.

Slow Response Times: Slow response times occur

when an application that used to respond to user input in a

fairly timely manner is now taking much longer to respond.

Application Lockup: Application lockup indicates

that the application appears, for all purposes to have locked up

completely and is no longer responding to any input. In some

cases, if you click on the apple icon in the far left of the

Finder menu bar and select the Force Quit…

option, the dialog that comes up may or may not indicate that

the application in question is no longer responding. In the

event the application may be waiting for input from another

source, such as a file on a hard drive that no longer exists

or a network connection that has closed, the Force Quit…

dialog will likely indicate that the process is still active.

Application Crashes: Application crashes can occur

when they start or during execution. If an application is

started and it soon exits, often for no apparent reason, the

operating system will often, but not always, report that the

application crashed. In other cases, the crash may resemble that

described above as an application lockup, but in this case the Force

Quit… option should be able to identify the application as

no longer running.

If any of these problems are consistent across all applications,

meaning all applications are having the same symptoms all the

time, then the problem is likely a system resource problem

(insufficient RAM or too little space left on the drive), a lack

of computing power, or possibly a hardware problem. If the

problems seem to exist erratically or only when certain other

applications are running, it's likely that there is one or more

application that's consuming too many system resources or

demanding too much from the system. Remember that the system can

launch processes without your being aware of it.

Performance problems can be caused by hardware problems (such as

a problematic hard drive,) insufficient resources such as a lack

of memory or free disk space, excessive load on the system, or a

CPU that can't really handle the load. Activity Monitor

typically can't help identify hardware problems, and these will

be addressed at the end of this article. We will focus primarily

on problems that Activity Monitor can help you identify.

Operating System Upgrade: Unfortunately, when a

new version of an operating system is released, it's often being

targeted at current hardware, not older hardware. The reality

may simply be that the system you own, even though it may be

identified as being "supported" may in fact not have the CPU

power to run the newer version of the OS efficiently, or with

the response times that you might have been used to on previous

operating system releases. If Activity Monitor is

showing no signs of problems, such as too much memory

consumption, excessive swapping, or too much disk activity, the

reality may be that the your system isn't really capable of

operating at the performance levels you might have been used to

with previous operating system versions. It is not uncommon for

a new operating system release to require the use of more memory

to run effectively.

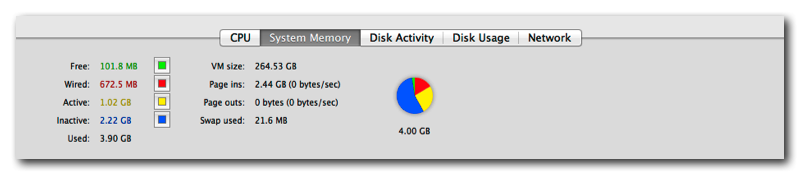

Insufficient Memory: If there's insufficient

memory in the system, Activity Monitor will display it

with page-outs and swap file sizes being greater that 0 when the

system is put under only a moderate load. Although Mountain Lion

states that it can run on 2GB of RAM, it doesn't necessarily

claim it will run well with 2GB of RAM.

Tests at the SCSC lab on a MacBook with 2GB, and then

4GB of RAM made this point clear. With 2GB of RAM, if several,

typical applications were launched simultaneously, such as

Safari, iTunes, Mail, and App Store, after using

the system for about 30 minutes, the page-outs went from 0 to

roughly 400MB, and the swap file size went from 0 to 2GB. When

the memory was increased to 4GB and the same experiment was

performed, the page-outs and swap file size remained at 0.

Paging out and swapping occur when memory runs short in the

system. To compensate for the shortage of memory, the system

writes inactive processes to the drive, and when they're needed

again, it reads them from the drive and loads them back into

memory, often swapping out some other process at the same time.

This process is time consuming and will bog the system down.

A quick overview of the memory being used by the system can be

found in the lower section of the Activity Monitor user

interface by clicking on the System Memory button. If

there is very little free memory available in the memory pie

chart, and the Page outs and Swap used fields

are greater than zero, memory problems should be considered a

viable performance problem suspect.

Insufficient Free Hard Drive Space: This is a

problem that most people are unaware of. If the free space on

their hard drive is insufficient, it will radically cut down on

the performance of the system, and can eventually make it

unstable. The operating system is constantly writing data files

to the drive without your knowledge. For example, when you put

the unit to sleep, the OS writes the entire contents of RAM to a

file named "sleepimage" (for those of you familiar with Unix

file operations, it's located in the

/private/var/vm/sleepimage file) and it is always the size

of your memory, thus if you have 4GB of RAM, this file will be

4GB in size. Additionally, other files, such as swap files, and

Time Machine "snapshot" files can eat easily eat up

gigabytes of data as well. During an operating system update,

there needs to be free space available to download the update

files, which can often be over a gigabyte in size.

At SCSC, for normally configured systems, the bare minimum

allowed free drive space is calculated using the following

formula:

2 X [System Memory Size] + 0.05 X [Volume Size]

For example, using the MacBook described in the experiment above

with a system memory of 4GB and a volume size of 80GB, this is:

2 X [4GB] + 0.05 X 80GB = 12GB

Note that this is the bare minimum drive space that should be

allowed for a volume and it's not set in concrete. The more free

space you have available on a drive, the better the performance

will be.

A quick overview of the amount of free space on the currently

active volume can be obtained using Activity Monitor by

clicking on the Disk Usage button in the lower section

of the user interface.

Excessive Drive Activity: Excessive drive activity

can be a side effect of a system with too little RAM, too little

free disk space, or it might be a process that's extremely drive

intensive. If there is too little memory in the system, the

excessive disk activity is caused by swapping memory contents to

the drive and back into memory because of the shortage of

memory. In the event a system has too little free space left on

the volume, the system must go through a process of hunting for

free blocks on the drive while simultaneously deleting any

temporary files it can in the process. In the event a disk

intensive application is running, which may be a system process

or a user added application, such as a database, the activity

will vary along with the activity of the offending process.

A quick overview of disk activity can be obtained by clicking on

the Disk Activity button in the lower portion of the Activity

Monitor user interface. This will display a sampled graph

of both data read and written between the drive and the system.

Excessive CPU Activity: Excessive CPU activity

typically occurs when one or more processes are demanding so

much from the CPUs that they interfere with other processes that

need CPU access as well. Another factor, that Activity

Monitor doesn't provide is called the priority of a

process. Processes with a higher priority, such as mds

in Mountain Lion, are given a very high priority and can thus

effectively hog CPU cycles away from other running processes.

CPU activity may be viewed for each CPU core on a system by

clicking on the CPU button in the lower section of Activity

Monitor. There will be a small, graphical window for each

active CPU core in the system. When the CPU activity is

excessive, each window can be virtually filled with user and

system activity. Each CPU core can contribute up to 100%

processing power, thus the number of CPU cores determines the

total percentage of power. A system with 2 CPU cores can thus

equal 200%, or 100% per core.

Excessive Network Activity: Excessive network

activity can be misleading, because in some cases, particularly

during web browsing, it may vary radically based on the web site

being visited as well as how much traffic is on the network.

Examples of other applications or activities that may cause

system slow downs based on high network activity can be

networked backup applications, database client applications, and

file downloading operations, to name a few.

Network activity may be monitored using Activity Monitor

by clicking on the Network button found in the lower

section of the user interface.

Too Many Applications Running: Unfortunately,

computers can't handle an infinite number of running processes.

The user needs to be aware of how much of a load an application

is putting on the system if performance problems start to exist.

The more memory and free disk space available, the more

applications you'll be able to run with fewer problems.

Insufficient CPU Power: Insufficient

CPU power can occur if the applications or system processes are

putting such an extreme load on the system that the CPUs are

constantly running at very high usage levels.

CPU activity may be monitored using Activity Monitor by

clicking on the CPU button found in the lower section of

the user interface.

Bugs: Software bugs can exist in both processes

acquired from a third party, and those coming with the operating

system itself. Bugs can often be difficult to trace or obvious.

In many cases bugs will become obvious because the application

will crash. In other cases, they may become "resource hogs" and

start consuming abnormally high amounts of RAM, start using

abnormal amounts of drive space, or make excessive use of the

CPU.

Hardware Problems: Hardware problems, such as a

hard drive with bad sectors on it can cause serious performance

problems. Such problems typically can't be addressed using Activity

Monitor and will be dealt with at the end of this

article.

Now that you're somewhat familiar with Activity Monitor,

we'll go ahead and use it to monitor a process. In this case,

we'll use a process that's frequently problematic, mds.

On Mountain Lion, if Spotlight is in full indexing mode,

it can cause the system to slow to a crawl, or even appear to

lock up a unit. For example, if we take the MacBook used

in the previous example and open a TextEdit.app session,

it normally starts in less than a second. With Spotlight

running in full indexing mode, we've seen TextEdit.app

take up to 20 seconds to start. The tell tale sign of Spotlight

indexing can be found by clicking on the Spotlight icon

(magnifying glass) in the upper right hand corner of the

display.

The mds process frequently launches other processes that

are either named, or start with the name mdworker. To

find these, do the following:

1. Click on the column named Process Name.

2. Scroll down to find mds.

3. Command click on the mds process and all others

beginning with or named mdworker.

4. Monitor these both when Spotlight indexing is

occurring and when it isn't.

The most important columns you need to pay attention to are

those labeled %CPU and Real Mem, and

secondarily CPU Time, Private Mem, Shared Mem, and

Threads. When Spotlight is in full indexing mode,

CPU use will skyrocket, disk activity will go very high, and the

amount of memory in mds will go from tens of megabytes

to hundreds of megabytes.

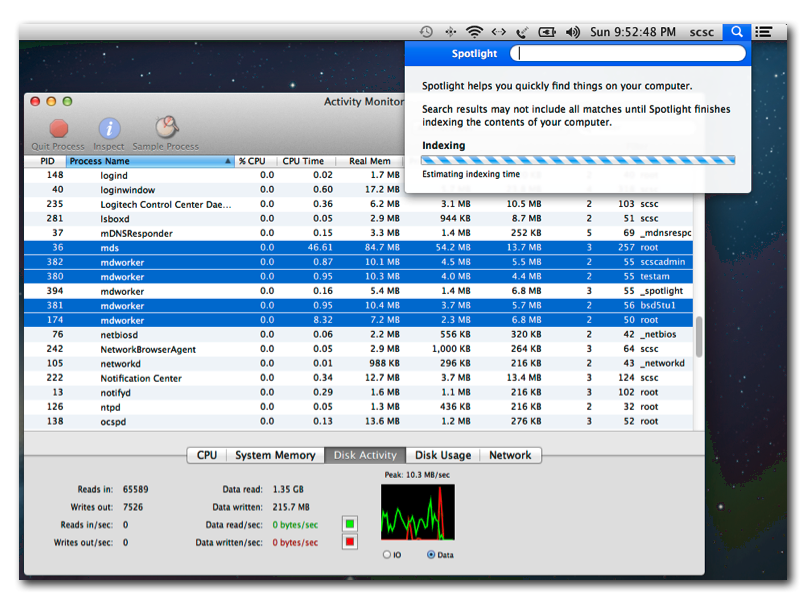

The following two images illustrate Spotlight in

its initial and full stages of indexing:

In the image above, Spotlight is in its initial indexing

phase. We've highlighted most of the mdworker threads,

but another popped up in the middle of the group as the screen

shot was taken. Notice at this time, the %CPU column

shows 0.0 for mds and mdworker elements, but

that the disk activity shown at the bottom of the display is

relatively high.

In the screen shot above, mds is now in full indexing mode. Notice that the drive activity is still high, but now the CPU consumption is increasing as well. When this occurs, many applications will come to a complete crawl. On laptops, the fans will kick on, and the battery consumption will increase.

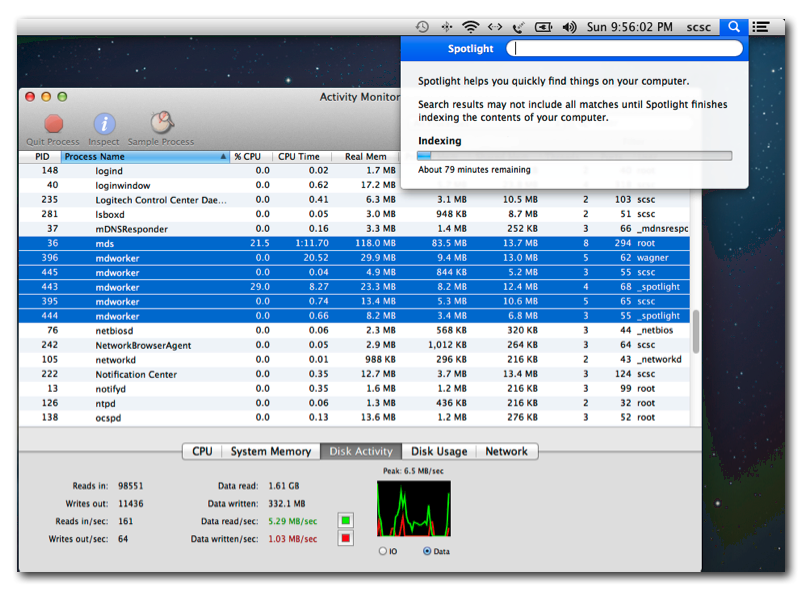

In the three partial screen shots of Activity

Monitor above we can observe how intensive mds is

when Spotlight indexing is occurring. In the first two,

we've selected the %CPU column, which illustrates the

highest CPU consumption going on in the system. Notice that in

the first shot, we see three mds related processes, and in the

second we see two. Notice also that in the second, the

percentage of the consumption for mds and mdworker

is a total of 126.3%. Remember, this system has two cores, thus

the total percentage can reach 200%. Over 60% of the total

processing power (126.3/200) is being spent doing

Spotlight indexing. The number of mdworker

threads can vary from zero to many at any given instance during

Spotlight indexing.

In the third screen capture, we see the CPU processing

that's going on in the CPU Usage graph. Although not pegged,

it's quite high.

In the screen capture of Activity Monitor above,

Spotlight indexing is complete. Looking at the

highlighted items, which were located by clicking on the Process

Name column header, the CPU consumption has fallen to 0%,

and there is only one mdworker thread "hanging around," but the

real memory being held onto by mds is not over 222MB. Notice

also that the CPU Usage graph in the bottom section of

the user interface is showing very little CPU activity. Over

time, it's not uncommon for the amount of real memory in mds

to reduce considerably when

Spotlight isn't in a full indexing mode.

In our opinion, when using Activity Monitor to identify

a performance problem, the most important items will be those

shown in the %CPU and Real Mem columns.

Additionally, the graphs located at the bottom of the Activity

Monitor user interface, particularly CPU, System

Memory, and Disk Activity

graphs should give a good indication of how heavily loaded

the system is. The information in the Private Mem,

Shared Mem, Threads, and Ports, may be of use to

you if you're looking at an "application gone wild." Get a feel

for how much processes use by clicking on each one of these

column headers in Activity Monitor to see what processes

typically use.

The CPU Time column can be simultaneously useful and

misleading because it tracks the total amount of time that the

CPU has dedicated to a process since started. If you terminate

an application, and then restart it, then the column entry will

only indicate the amount of CPU time spent on the most recent

launch of the application. Processes such as kernel_task

that are running all the time will almost always be at or near

the top of the list if this column is selected. If you launch an

application, its CPU TIme entry will always initially be

0. If, in a matter of minutes it's accelerated its way to the

top of the list, then it indicates that the CPU is spending an

incredible amount of time hogging CPU resources. The mds

process will do this when it's in full indexing mode.

The best way to learn to use Activity Monitor is to

simply use it and get used to how it monitors processes. If

you're not inclined to wait for a Spotlight indexing

session to begin, another route would be to bring up Safari

and start watching a high def video on something like YouTube.

In this case, you would want to focus on Safari, Safari Web

Content, and the Flash Player.

Some of the common problems we've observed are described below.

In some cases, these aren't operating system, process, or even

system problems. Some of the problems we've seen people

encounter are caused by external problems or even user error or

unawareness. Here is a list of some of the more common problems

we've encountered:

Web sites and ad servers: Many websites

that display ads, especially lots of ads, are feeding a web

browser not only information from their own web site, but also

piping in web data from ad servers. Ad servers may be located

anywhere in the world, and in most cases they're not hosted on

the web site being visited. If network traffic to one or more ad

servers is heavy, the overall response of the browser may be

slow. If the page being visited won't complete loading until the

ad server completes its loading, this can mislead the user into

thinking that the browser or the system are at fault, when in

fact it's the site being visited.

This problem will obviously only occur when web sites are being

visited. In some cases, the ads themselves may be playing video

and launching a Flash Player, and these things take CPU,

memory, and network resources. The most obvious cure for this

problem is to, if possible, go to another web site that has the

same information but fewer ads. If evaluating it using

Activity Monitor, you would want to monitor the Safari

and Safari Web Content processes, and possibly the Flash

Player (or another media player if applicable) for

resource consumption. You would also want to monitor the Network

graph in the lower section of Activity Monitor's user

interface to see if the network is being tied up or saturated.

Pay attention to the "peak" level on top of the network graph,

because it will change with loading.

Unawareness of relaunched applications: With the release

of both Lion and Mountain Lion, one problem that we've observed

is that some people are unaware of the fact that when they shut

their system down, unless told not to do so, the operating

system will open up and start all the applications they had

running in the previous session. If they're using multiple work

spaces and the applications are assigned to specific work

spaces, the user is oblivious to the fact that they may

inadvertently and unknowingly launching numerous applications.

They find the start up times and login process abysmally slow.

They then start opening up other applications which simply

exacerbates the problem.

Activity Monitor will make this clear, but it shouldn't

really be needed, since switching from desktop to desktop

usually makes the user aware of the problem. Activity

Monitor output might be useful, however, if one of the

applications is problematic or the problem is being dealt with

from a remote location.

Spotlight and mds: This was described in the

previous section. If applications suddenly come to a crawl,

they're taking seconds or tens of seconds to open or react to

input, there's a good chance Spotlight indexing is

taking place. As described previously, this can be detected

using Activity Monitor.

Safari Web Content (Mountain Lion): Safari Web

Content appears to have some strange bugs that seize a

considerable amount of memory for no apparent reason. In one

instance, we've observed it eating up nearly 100% of the free

memory on a system forcing the system to a crawl. This bug is

difficult to replicate. If we could replicate it we'd send a

report to Apple, but it seems to occur erratically and not

frequently, but we've seen it reported on other systems as well.

In this case, application loading and response times will be

slow. Activity Monitor will present this to the user

with an extremely high amount of memory being consumed by the

process as seen in the Real Mem column of the process

table. The System Memory graph in the lower section of Activity

Monitor will display little, if any free memory. The

solution is to terminate Safari and if needed, use the

purge command to reclaim memory (using purge is described

later.)

Flash Player Safari Plugin: Depending on the video

being viewed within Safari, this process can consume

considerable amounts of memory and show high levels of network

traffic, disk activity, and CPU cycles. This is more or less

dependent on the video being viewed because low bandwidth video

won't consume very many resources, but high def video will. This

will can be a potential problem if you have a lot of other

applications running and a system with weaker processing

capabilities, less than optimal RAM, or a lack of free disk

space.

When you click on the System Memory button of Activity

Monitor, you'll be presented with a pie chart showing the

amount of memory in the system, and how it's allocated. It will

look similar to the following:

Some people become alarmed, when instead of seeing a graph as

shown above, with a reasonable amount of free memory available,

they're greeted with the following:

People become (unnecessarily) alarmed by this because it appears

there's virtually no free memory on the system. This isn't true,

it's just a characteristic of the operating system. The memory

above shown in blue, which is called Inactive Memory is

free memory. When a process launches, gets used, and then ends,

the original memory is not automatically put back into the free

memory, but often the Inactive Memory. The system does

this so that if the application is launched again, instead of

having to reload everything all over again, it simply uses what

was there from the original launch of the process. If other

processes are launched by the system and they need that memory,

the system will turn it over to them.

If you find this troublesome, there's a system command named

"purge" that will completely free up all the "blue memory" shown

above. purge must be run from a command line (Terminal) window,

which can be accomplished as follows:

1. From the Finder

menu bar, click on "Go"

2. From the pull down

menu, select Utilities.

3. From the Utilities

folder that comes up, double click on Terminal.app

4. A terminal

application will open up.

5. Type the word

purge and hit the return key.

If you have an Activity Monitor session up and running

you will see that the "blue memory" disappears and becomes free

memory.

If you've analyzed your system using Activity Monitor

and can find no problems with the operating system or any

running applications, there may be hardware problems with the

unit. If the problems are characterized by delays, "spinning

beach balls," and occasionally a message from the operating

system indicating that it can't read or write to the drive, the

odds are that the hard drive has problems. In some cases, system

parameters can become corrupt over time and cause the system to

behave erratically.

Here at SCSC, we offer a product named Scannerz for Mac OS X

that performs hard drive and system fault tests on Apple

computers. If you suspect you're having drive or drive related

system problem, click HERE

for information on Scannerz.

If you think your system might need to be reset, the following

links to Apple's support site might be of use to you:

Resetting

NVRAM and PRAM

Resetting the

System Management Controller

Generally speaking, there are very few items on a contemporary

system that can fail without being obvious to the end user. If a

logic board fails, the system won't start, or if it does, it

won't stay active long. If a video, network, keyboard, or other

attached peripheral or card fails, that too is usually obvious.

If drive tests and system resets can't isolate the problem, we

would recommend having the unit checked out by a professional.

Scannerz, Scannerz Lite, FSE, FSE-Lite, Performance Probe 2,

Phoenix, SpotOff, and Spot-O-Meter are Mac OS X universal

binaries and support both Intel and PowerPC G4 and G5 based

systems using Mac OS X versions 10.5 (Leopard), 10.6 (Snow

Leopard), 10.7 (Lion), 10.8 (Mountain Lion), 10.9 (Mavericks),

and 10.10 (Yosemite). PowerPC based systems must use Mac OS X

10.5

Supported Intel based systems include all variants of the

MacBook, MacBook Air, MacBook Pro, iMac, Mac Pro, and Mac Mini.

Supported PowerPC based systems must be running MacOS 10.5

(Leopard) and include the iBook, Power Mac, eMac,

iMac, Mac Mini, and PowerBook G4 Series.